Lord of the Rings: The Animated Musical | Architecture: Bag End

In this week’s essay, my loves of historic house tours and The Lord of the Rings combine for the first time as I present my map of Bag End, also spelled Bag-End by the older generations of Hobbits. Since Tolkien was a philologist, it is fitting to take a brief break to explain the naming scheme around the property, along with the clan name of the family who built it. Tolkien studies expert Tom Shippey noted in The Road to Middle-earth that “bag-end” is a literal translation of “cul-de-sac”, which was further elaborated upon by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull in Reader’s Companion. The current meaning of a road terminating at a house or collection of houses dates from 1819.

As for the surname Baggins, Shippey sent readers to the Oxford English Dictionary, which pointed out that this was a colloquial term in parts of northern England “for food eaten between regular meals… afternoon tea” since about 1746. However, I discovered another archaic meaning: “to look askew… to leer” or to be squint-eyed, which appeared around 1369 to 1380. The reader may recall my opinion in “Races: Men, Part 2” that when Frodo complained about “a squint-eyed ill-favoured fellow” (The Fellowship of the Ring, 176) while sitting in the Prancing Pony tavern of Bree, he was hypocritical in referencing the man’s “sly, slanting eyes” (Fellowship, 204). I originally mentioned his Scandinavian-coded given name and Stoor ancestry — Hobbits who had immigrated from the Asian-coded region Dunland — as evidence that he had the same almond-shaped eyes as the Man being judged. This new evidence could indicate that this trait was also present in the Baggins branch of his family; since Tolkien wrote part of the Oxford English Dictionary and reminded others of this fact, I cannot rule this option out.

Back to what the reader came for, plenty of professional and recreational architects have tried their hand at designing a likely layout for the beloved Baggins family home. Tolkien drew the exterior of the building in his watercolor painting “The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the-Water” which appeared on the cover of the 1938 American edition of The Hobbit, along with a black-and-white drawing of “The Hall at Bag-End, Residence of B. Baggins Esquire”, which seems to struggle with proportion. Karen Wynn Fonstad published her version of Bag End in The Atlas of Middle-earth. This detailed a possible location of the party field and party tree, along with how Bagshot Row was turned into a quarry during the regime of Saruman. Weta Workshop created props and practical effects for Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and designed a floor plan. This example appeared more jumbled than the neat layout described by Bilbo in the first few pages of The Hobbit, along with lower ceilings than suggested in Tolkien’s drawing, and so I will not refer to this version anymore.

My own layout, which I will thoroughly describe during the conclusion of this essay, trends closer to the Fonstad design but also takes inspiration from the many historic houses I have visited. I will posit that Bag End underwent renovations during its hundreds of years as a residence, and the property in its final state as occupied by the Gardner descendants may have become unrecognizable when compared to the original construction by Bungo Baggins. My replica, therefore, must be a restoration to a specific point in the timeline, presumably after Bilbo and Frodo had put their own decorative touches on the property, but before the Gardner family dug extra rooms to accommodate their many members.

A Brief History of Subterranean Dwellings

Hobbits, Dwarves, and Elves enjoyed dwelling underground, much like our ancient ancestors in the Real World who may be colloquially referred to as “cave people”. Subterranean dwellings may have been among the first shelters for early humans. At Lascaux Cave in the Vézère Valley of France, now considered a UNESCO World Heritage Site, archaeologists research paintings created up to 21,000 years ago that depict extinct forms of wildlife, while visitors can tour a replica. Also in France is Chauvet-Pont D’Arc Cave in the Ardèche Valley where paintings are even older, dating between 35,000 and 43,000 years ago.

The Sassi di Matera in Italy is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that has been occupied, possibly continuously, since the Paleolithic era, or around the same time as the caves in France. This unique town shared many striking similarities to hobbit towns and multi-family dwellings. According to a 2014 article by writer-historian Tony Perrottet appearing in Smithsonian Magazine, local people in the Sassi call themselves troglodytes from a Latin word meaning “cave-dwellers”, similar to the “translated” word holbyltan meaning “hole-builder”, which the Rohirrim used for hobbits. The caves are lovingly referred to as warrens by the residents; in contrast, West Farthing hobbits use the term disparagingly while referring to Brandy Hall in Buckland. The term “warren” has developed a dual meaning in English with a “piece of land for breeding of rabbits” appearing around 1400, while the more general “cluster of densely populated living spaces” came in the 1640s. Today, the caves are modern homes, businesses, and tourist attractions with electric lighting and internet access. Even so, Perrottet could not resist remarking that the former family dwelling of his new friend, Signor Domenico Nicoletti, “looked like a hobbit’s house”.

Yet another UNESCO World Heritage Site is Göreme National Park and the Rock Sites of Cappadocia in Turkey, where people lived as far back as the 4th century AD. Early Christians who followed St. Basil the Great lived in these caves, while later generations from the 8th century through the 13th century decorated the stone walls to create monasteries and churches, also known as “rupestral sanctuaries”. I could not find an exact date that the rare term “rupestral” entered English from Latin to mean “rock”, but it appears to be used mainly when describing cave art, including tombs and paintings. Also in the area are “fairy chimneys” or “hoodoos”, a tall and narrow rock created when soft stone is eroded away, and hard stone remains. I saw hoodoos in 2018 while at Bryce Canyon National Park in Utah, and while not explicitly described in the original Legendarium, I think these deserve inclusion in my own interpretation.

Finally, Coober Pedy in South Australia is a modern example of underground living. Self-proclaimed as the Opal Capital of the World since 1915, about 2,500 people currently live in the mining town. The official website explains that Coober Pedy is “an aboriginal term meaning ‘white man in a hole’” but does not cite the language of origin. The reason for underground living is the desert temperature, which hits 126°F (52°C) in the middle of summer; in contrast, the dwellings average 73°F (23°C) all year. Unlike cozy hobbit holes with their round windows, the homes of Coober Pedy have little ventilation and tend to be dry. The roofs of these houses occasionally cave in, the same fate suffered by poor Will Whitfoot, the Mayor of Michel Delving, who was caught in “the collapse of the roof of the Town Hole… had been buried in chalk, and came out like a floured dumpling” (Fellowship, 177). For all the silliness involving little people living in holes, Tolkien must have done his research when inventing their houses.

The Evolution of the Manor

Historically, English manor houses were the homes of the feudal lord and his family in a system known as manorialism. These types of properties went by many names depending on design features and location but could also be known as a castle or palace, châteaux, country house or mansion, and stately home. The manor was often located close to a village ruled by the lord so he could take advantage of its many amenities, including markets and workers. Manors generally had large amounts of surrounding property such as orchards, vineyards, fields for grazing livestock, and a hunting forest. These were originally maintained by serfs or unfree laborers and later by paid staff. Older homes were fortified to protect against attacks by rival feudal lords, but newer homes were more open.

Many of these beautiful properties are now open to the public as museums. Famous Newstead Abbey was originally a monastery constructed in 1170 by Henry II. The building was given to feudal lord Sir John Byron in 1540 during the Dissolution of Monasteries, an order by Henry VIII after he left the Catholic Church and founded the Church of England because he wanted a divorce. By the time of libertine poet George Gordon Byron, who lived from 1788 to 1824, the property had been in the family for around two hundred and fifty years, which is longer than the United States has been a country. Byron apparently did not care about this heritage and sold the property. After changing hands throughout the 19th and early 20th century, Nottingham City received the mansion as a gift in 1931 and turned it into a museum.

Lord Byron was not the last of the nobility to sell his heritage. Eight years after his death, England changed its voting rules with the Representation of the People Act 1832, usually called the first Reform Act or Great Reform Act for short. The recent French Revolution had scared the nobility of Europe, and the ongoing British Industrial Revolution was creating a rapidly increasing middle class who wanted political power. The ability to vote was broadened to men who owned land, rented a farm, or kept a shop, while the handful of women who were previously permitted to vote had this right taken away. Leading this effort was Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, who also aided in the passage of Slavery Abolition Act 1833 and in pop history articles is considered the namesake for tasty Earl Grey tea.

Across the water in the United States, the construction of manors followed a different timeline. European families did not begin colonizing the area until 1620, and early houses were primitive. However, by the time of the American Industrial Revolution, wealthy factory owners, transportation magnates, and oil barons wanted their own piece of old Europe on American soil. While the founding fathers frequently built mansions to oversee their slave-run plantations — including George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, and James Madison’s Montpelier — they were nothing in comparison to the mansions appearing in Newport, RI and the Biltmore in Asheville, NC at the height of the Gilded Age. These investors purchased entire rooms of European manors and reconstructed them within their own home.

A few European industrialists and bankers did build their own manors during the Victorian Era. Among the most prominent of these were members of the Rothchild family. Their properties were built throughout western and central Europe along with the United States. Because of their skill in banking and ability to aid governments in crisis, many men were granted hereditary titles. Despite being among the few practicing Jews to reach such a high social and political rank, they were not protected from antisemitism. Between everyday discrimination, targeting by the Nazis during the Holocaust, and economic downturn, the family lost many of their properties during the 20th century.

Bag End shows elements of both the classic English manor and the industrial manor. Belladonna Took was the favorite daughter of the feudal lord, Thain Gerontius Took, and likely received this land as a wedding gift. She may have owned the entire Hill where Bag End was dug, or even all of Hobbiton and Bywater with shop owners and tenant farmers paying annual rent. During “The Scouring of the Shire” in The Return of the King, members of the Gamgee-Cotton clan showed high respect to Frodo Baggins, the master of Bag End at the time. Since this clan was made of laborers who worked on the Bag End property and local farmers, possibly tenant farmers, who felt obligated yet honored to house Frodo during the restoration of Bag End, I believe the wider breadth of ownership is likely.

Belladonna’s husband, Bungo Baggins, appeared to not come from nobility but industry. He evidently had a background as an architect and taught his son, Bilbo, how to keep a business-like manner while money lending, not unlike the banking Rothchild family. The existence of three small properties at Bag Shot Row below Bag End pointed to either long-term rental units as a means of generating income even if noble power dried up or to basic housing for laborers. The only known occupants of these properties were stated at the time of Bilbo’s eleventy-first birthday with apparent renter Daddy Twofoot living at 2 Bag Shot Row and Bilbo’s retiring gardener Ham Gamgee living with his youngest son Sam at 3 Bag Shot Row.

A Tour of Bag End

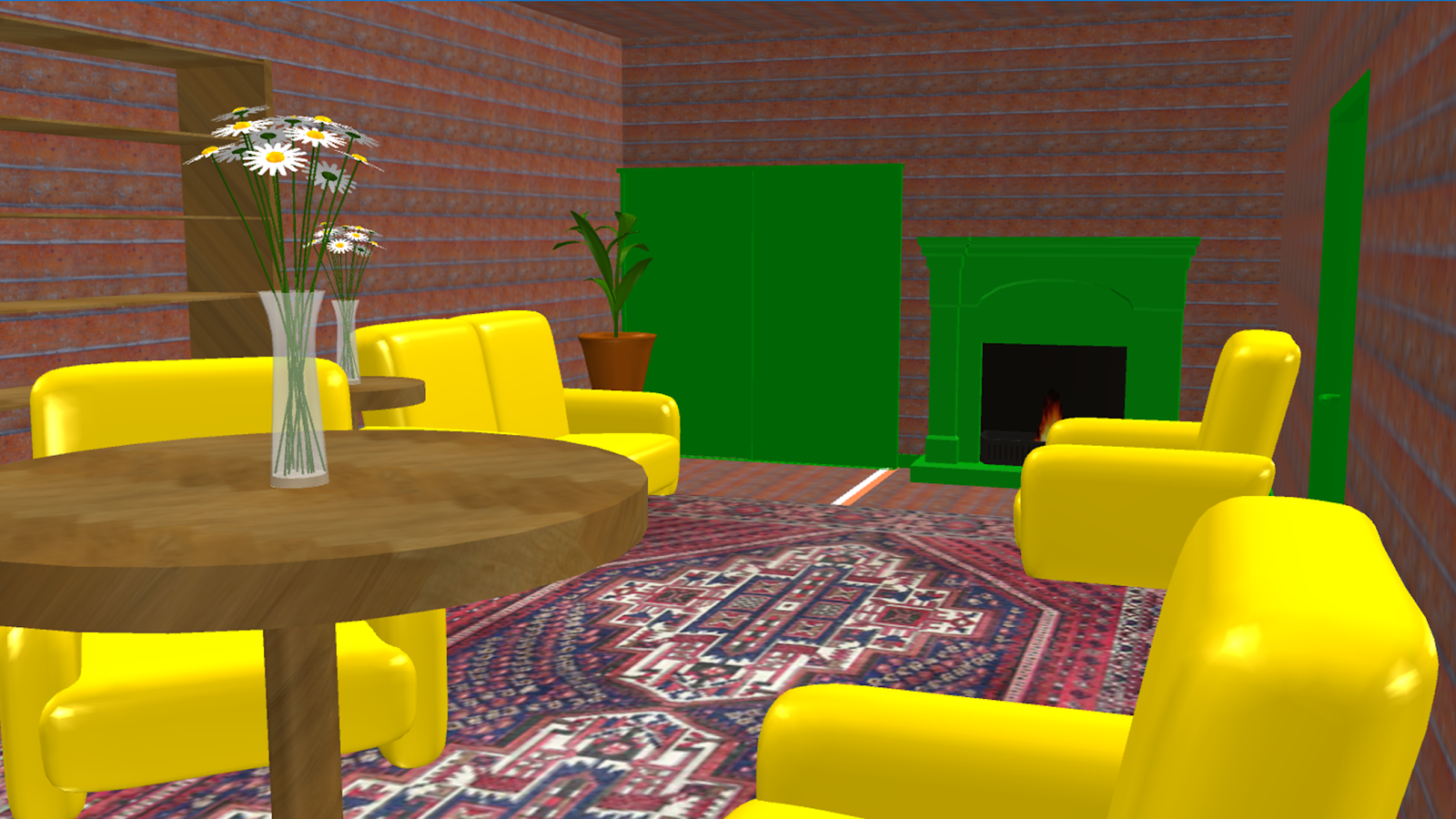

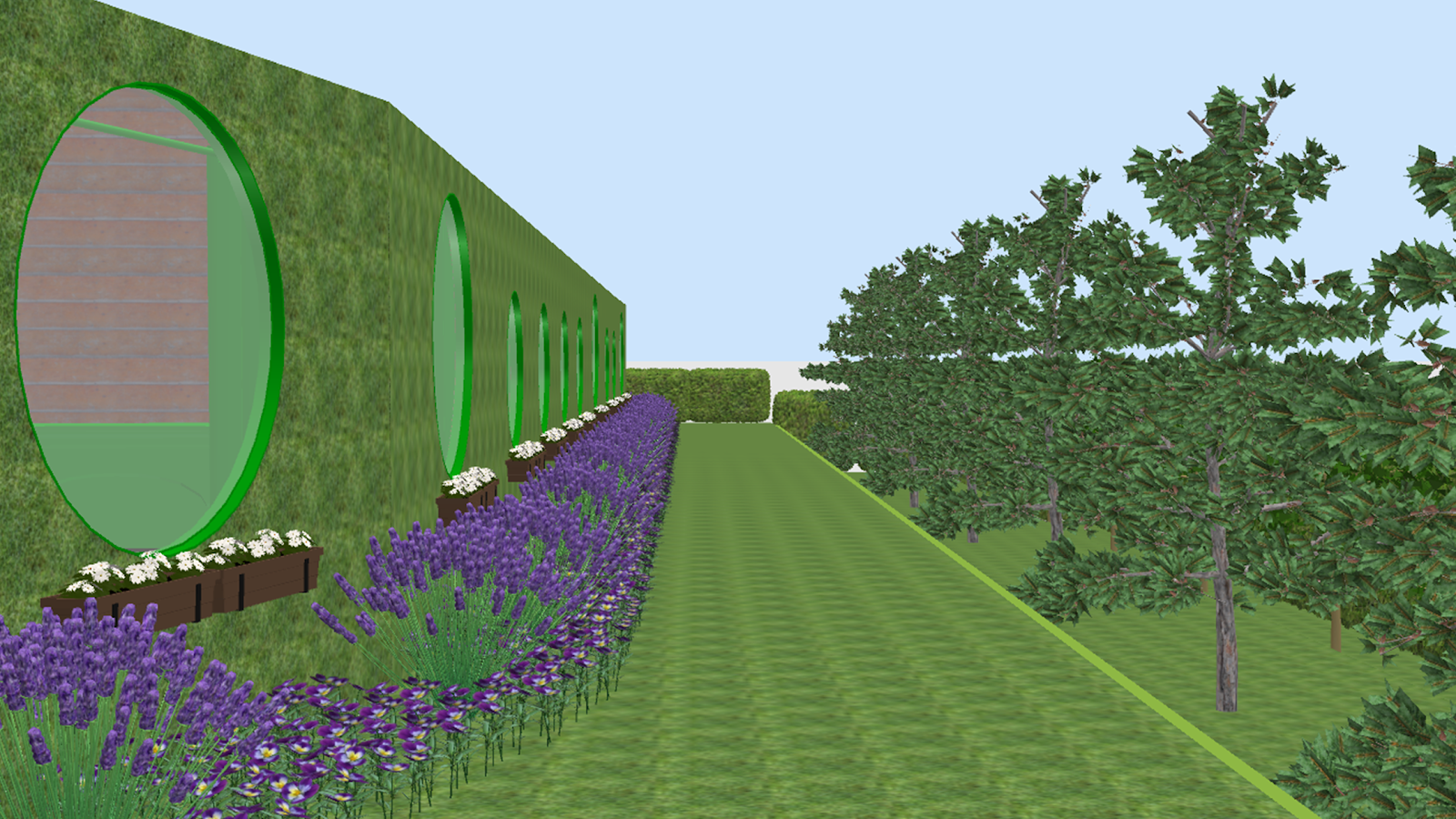

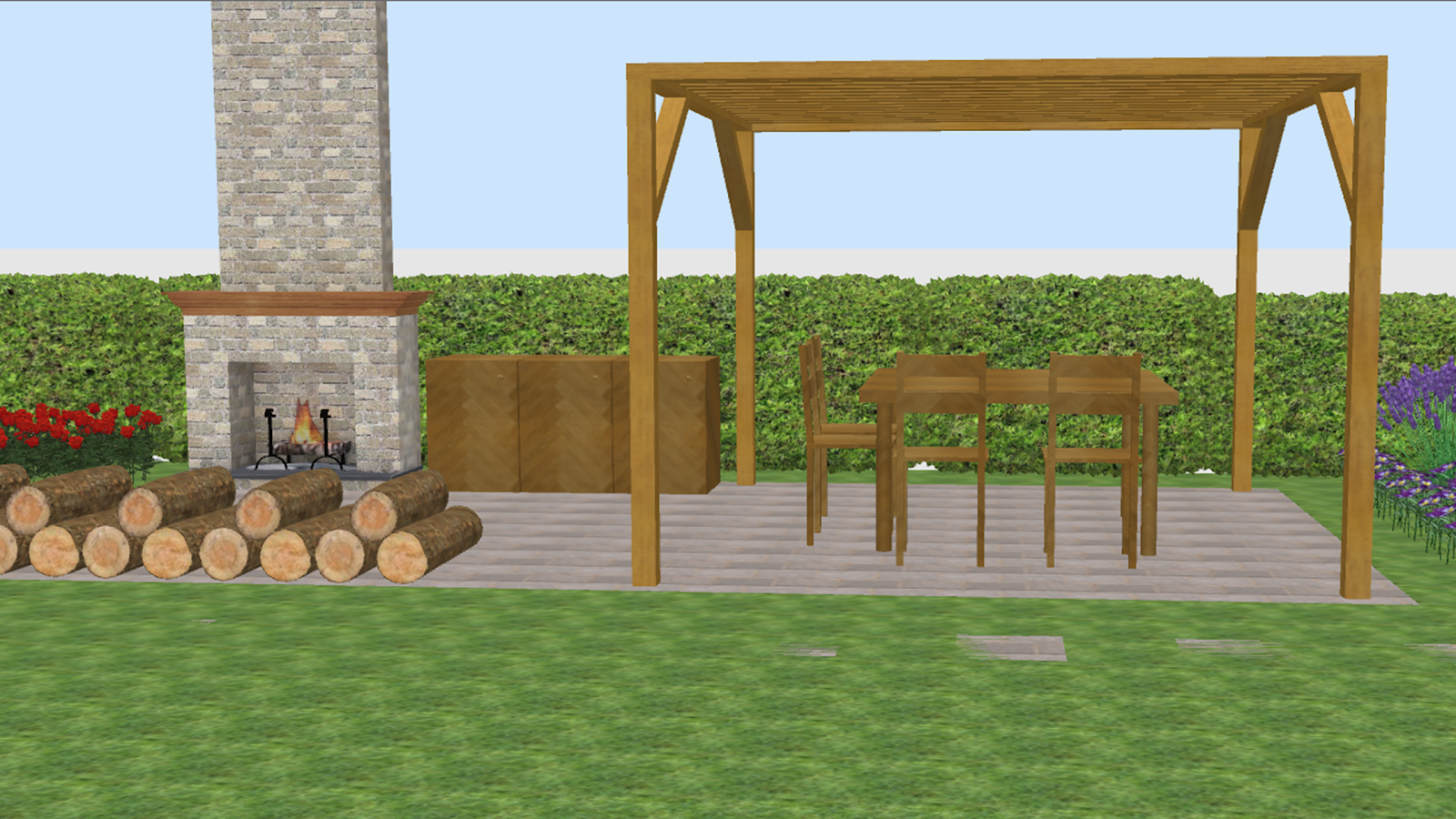

Welcome to my digital replica of Bag End. I used a free interior design program called Sweet Home 3D to create an approximation of how my version of Bag End is laid out, including choices for flooring, paint, furniture, curtains, and other types of décor. Not all elements in this 3D model are accurate; for example, I could not find any round doors in the Sweet Home 3D library, so you will have to pretend that the regular rectangular doors are round. Additionally, some fabric patterns and colors would appear differently in the animation than in the model. Along with screenshots of the tour, I have included a few samples of animated spaces with atmospheric lighting, which I created in Adobe Illustrator. This should give the reader a better sense of the color palette and mood for the hypothetical musical. I have taken some artistic liberties with explanations of design elements, but they are consistent with Real Life stories I have heard on house tours.

The house has been restored to its condition during Shire Reckoning (S.R.) 1401 to 1418 when Frodo occupied the residence alone except for his annual celebration of Bilbo’s birthday when he invited twenty friends and the constant maintenance works done by Sam. Upon entering Bag End through the front door, the visitor walks into the Great Hall. Other readers have noted anachronistic or overly modern elements in Tolkien’s illustration, as a clock and a barometer hang on the walls along with many pegs for hats and cloaks. I personally believe Bilbo would have ordered a custom cuckoo clock to honor his Dwarf friends, where their signature song “Far over the Misty Mountains cold” played on the hour, and thirteen figures danced through a little door above the clock face. Cuckoo clocks were made in Germany beginning around the mid-17th century, making them an ideal piece of post-medieval Germanic décor. As for the barometer, Italian physicist Evangelista Torricelli may have invented it during the 1640s, around the same time as cuckoo clocks. While I have not depicted these in the current model, they should appear in detail in future illustrations. Most public activity happens in the Great Hall and the rooms on either side. The double doors to each room can be swung open to create a larger space. The hall has enough space for half a dozen couples dancing plus a “hobbit quintet”, which might include two tiny violins, a little viola, a small cello, and a tin whistle.

The room to the left of the Great Hall is the Front Parlor, sometimes known as a drawing room, while the room to the right is the Grand Dining Room. This arrangement was fairly common in mid-sized mansions during the 19th century; Historic New England’s Roseland Cottage in Woodstock, CT has a floor plan mirroring this portion of Bag End. After a grand dinner, the hobbit-lads tended to remain in their seats to smoke and talk business, while the hobbit-lasses retired into the drawing room to play cards and share recipes, although it was equally likely for both groups to do all four activities. The hobbit children either remained in the Great Hall to play games, went outside to play in the lane, or hung on the bell until their parents came out to scold them.

The long hall through the back portion of the house was reserved for intimate family and closest friends. We will visit the rooms on the right going down to the gardens and visit the rooms currently on our left coming back. The first room is the Main Kitchen used primarily during large meals with several guests. For most wealthy households in Europe from the medieval period through the Industrial Revolution, servants would have occupied this space. Although they often became so devoted to their employers that some considered their duties “a form of marriage”, servants typically ate and slept in different spaces than their employers. However, hobbits held cooking and eating in such high esteem that the hosts of a party would prepare the food themselves, as seen in the way Bilbo fed visiting Dwarves during “Chapter 1: The Unexpected Party” in The Hobbit. Only the closest and most trusted servants were given such an honor, shown through Sam cooking meals for Frodo and the cousins throughout The Lord of the Rings. Connected to the Main Kitchen via a sliding pocket door is the Main Pantry with a ladder leading down to the Cellar. The behind-the-scenes servant’s quarters tour extension is well worth the additional time, so I will take you down there at the end of this tour.

A guest bathroom is located next to the Main Pantry rather than accessible from the Great Hall, suggesting that this was reserved for overnight guests and preventing dinner guests from overstaying their welcome. This bathroom seems to have been installed with indoor plumbing from the time of construction. Among the oldest plumbing systems known in the Real World were built in ancient Rome around 200 B.C. Unlike today when most municipalities require running water for a house to be considered livable, these ancient systems only existed in public bathhouses or the mansions of the wealthiest residents. While convenient for bringing in water and flushing waste, pipes were made of lead and likely poisoned both its intended users and local wildlife. In the United States beginning in the late 18th century, aqueduct companies used wooden pipes to transport water; I saw a remnant of one during my first trip to Strawbery Banke in Portsmouth, NH in October 2022. Since Hobbits tend to be an eco-friendly bunch, they likely used wooden pipes for their plumbing.

On the other side of the Guest Bathroom is the Private Kitchen, a smaller cooking area where close family and friends would have been invited to make their meals. This kitchen has its own pantry and ladder down to the Cellar, along with a door connecting it to the Private Dining Room. The small table allows for no more than six chairs. During the first Gardner generation born at Bag End, this dining room likely became a bedroom. Hobbit historians continue to debate what cooking technology was originally installed in the house, and how the appliances were updated over time. The first Baggins generation may have cooked over an open fire using a large, red brick fireplace with a pair of bread ovens, while the Gardner family installed a full Stone City kitchen inspired by the setups they saw in Minas Tirith, Gondor. The round iron roaster, cooking range, and multiple smaller stoves resembled the Rumford kitchen setup found at Historic New England’s Rundlet-May House in Portsmouth, NH and Hearthside House in Lincoln, RI.

Past the Private Dining Room is the Back Parlor, famous for its role in Book I, Chapter 3 “The Shadow of the Past” in The Fellowship of the Ring. Here is a good spot to explain the mechanics of Bag End windows. These are sash windows where the glass panes slide vertically, an invention from mid-17th century Britain in the Real World. All the windows at Bag End have working shutters, which could be closed to block out light and unwanted eyes or to keep in heat. If you think you see no shutters on the exterior of the house, you are correct! The classic board & batten shutters popular on original American Colonial and Colonial Revival style houses would add to the difficulty of mowing the grass, and the round shape of the window would have allowed for only one connection point between the shutters and the trim. Instead, the windows have cleverly hidden pocket shutters that slide out from the wall across the glass and are closed from the inside of the house. The windows also have curtains to serve a similar purpose along with adding a decorative element to the room.

Now we enter the Garden, which has been restored to the height of the Gardner era. Botanists Walter S. Judd and Graham A. Judd completed a comprehensive study called Flora of Middle-earth: Plants of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Legendarium that described the wide range of native plants found throughout Arda. Highlights of this garden include roses, lavender, daisies, violets, and a variety of trees, along with thick hedges to keep out naughty hobbit children trying to steal apples. The landscape style is similar to a traditional English garden, which appeared around the 18th century in an attempt to make a curated landscape indistinguishable from nature. A waterfall flows from the stone fountain, combining a seemingly natural element with a Neoclassical element inspired by the White Towers of Westmarch, which were restored during the Gardner era.

Returning back inside, the first office on the right belonged to Frodo and served as his main location for writing and compiling what became The Red Book of Westmarch; this office was preserved to that time period throughout the occupation of the house. The room next door was likely the office of Bilbo, which became a bedroom in the Gardner era. The current dartboard on display has anachronistic Arabic numerals instead of Cirth numerals, but it does demonstrate Bilbo’s love of games, especially when he should have been working. The next three rooms were closets during the Baggins era but became bedrooms during the Gardner era. The closet with the ensuite bathroom was likely regarded as the “Best Bedroom” where Thorin II Oakenshield, King of Durin’s folk, stayed during his trip to Bag End.

Finishing up on this hallway are the main bedroom and the secondary bedroom. Historic paint analysis revealed an unusually colorful layer in the secondary bedroom dating around S.R. 1380 that was replaced with a soft yellow around S.R. 1480. Cross-referencing the paper record, the unique paint was applied soon after the arrival of Frodo Baggins to Bag End, and the subdued layer appeared soon after the departure of Sam Gardner when his son, Frodo-lad Gardner, inherited the property. Conservators did their best to replicate the saturated colors during the restoration.

For the extended tour, we must go outside and travel along the lane, then take a left down a narrow path to the servants’ door to reach the cellars. These are located underneath the living quarters of Bag End but above the houses of Bag Shot Row. The three small hobbit-holes were restored to their original form since they were turned into a gravel quarry in S.R. 1419 and are available to tour separately. Much like the upper portion of the property, this lower level is lined with red brick for added stability. Standardized red bricks appeared in Europe during the 4th century BC as Greek building techniques had been spread throughout the region after the conquest led by Alexander the Great. Modern red bricks appeared in the 19th century during the Industrial Revolution as family-run kilns were replaced by massive factories. Bag End bricks would have been handmade by artisans throughout the West Farthing. By the time Saruman controlled the brick factory in Hobbiton, the building materials were likely manufactured at a large industrial site and were possibly imported. This stop ends the tour of Bag End.

While visiting Bag End is delightful, not everyone can enjoy the indoor portion of the experience. Unfortunately, like most historic houses, the building is not accessible to those using a wheelchair but for a different reason than typical. Most historic houses have steep stairs leading into the house and connecting floors. The two levels of Bag End have ground level entrances, but the doors are round, blocking wheels from crossing the threshold. Interestingly, wheelchairs did exist in the Shire; Tolkien reported in Letter 214 that Lalia “the Fat” Clayhanger Took used a wheelchair in her later years, only to be tipped down the garden stairs by an attendant, likely Pippin’s oldest sister Pearl, and die of her injuries.

Bag End has low lighting, especially in the windowless rooms, on evening tours, and on rainy days, as electricity was never introduced to the Shire. Headroom is not as much of an issue as one might initially assume, as ceiling height is generally seventy-eight inches (198.12 cm), while the long hallway is wide at 60 inches (152.4 cm), far exceeding the 36 inch (91.4 cm) minimum standard in modern Man homes. Finally, signage and brochures are only available in Westron at this time. For those who enjoy historic house tours and fantasy fiction, Bag End is a great stop. Currently, doors are open to all at any time, and tea is at four.

Watch a virtual tour here:

Abby Epplett’s Rating System

Experience: 9/10

Accessibility: 6/10

Read past installments of Lord of the Rings: The Animated Musical

- New Project Announcement

- Introduction by Peter S. Beagle

- Foreword by J.R.R. Tolkien

- Introduction to the History of Animation

- Prologue, 1 Concerning Hobbits

- Introduction to Maps

- Races: Hobbits

- Perspectives on the Sea

- Prologue, 2 Concerning Pipe-weed

- Prologue, 3 On the Ordering of the Shire

- Prologue, 4 Of the Finding of the Ring

- Prologue, Note on the Shire Record

- Introduction to the History of Musical Theater

- Introduction to the History of Documentaries

- Introduction to the History of Conlangs

- Introduction to the Appendixes

- Overview of Appendix A “Annals of the Kings and Rulers”

- Appendix A, I The Númenórean Kings, (i) Númenor

- Appendix A, I The Númenórean Kings, (ii) The Realms in Exile

- Appendix A, I The Númenórean Kings, (iii) Eriador, Arnor, and the Heirs of Isildur

- Appendix A, I The Númenórean Kings, (iv) Gondor and the Heirs of Anárion

- Appendix A, I The Númenórean Kings, (v) The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen

- Lord of the Rings: The Animated Musical | Races: Elves

- Appendix A, II The House of Eorl

- Appendix A, II The Kings of the Mark

- Races: Men, Part 1

- Races: Men, Part 2

- Appendix A, III Durin’s Folk

- Races: Dwarves

- Appendix B: The Tale of Years

- Races: Orcs

- Appendix C: Family Trees

- Appendix D: Shire Calendar

- Appendix E, I Pronunciation

- Appendix E, II Writing

- Races: Maiar, Wizards & Balrogs

- Races: Maiar, Environment & Craft

- Appendix F, I The Languages & Peoples of the Third Age

- Appendix F, II On Translation

- Christopher Tolkien Centenary Conference

- Races: Valar, Part 1

- Races: Valar, Part 2

- Races: Valar, Part 3

- Framing Device