Museo del Hombre Dominicano

During my trip to the Dominican Republic in June 2023, I visited Museo del Hombre Dominicano [Museum of the Dominican Man] in Santo Domingo. This museum is located in the cultural district of the capital not far from Museo de Arte Moderno de la República Dominicana (MAM) [Museum of Modern Art of the Dominican Republic], which I visited at the beginning of my trip to the city, and recently underwent renovation and exhibit redesign. Both floors of exhibits are new and give a modern perspective to Caribbean history.

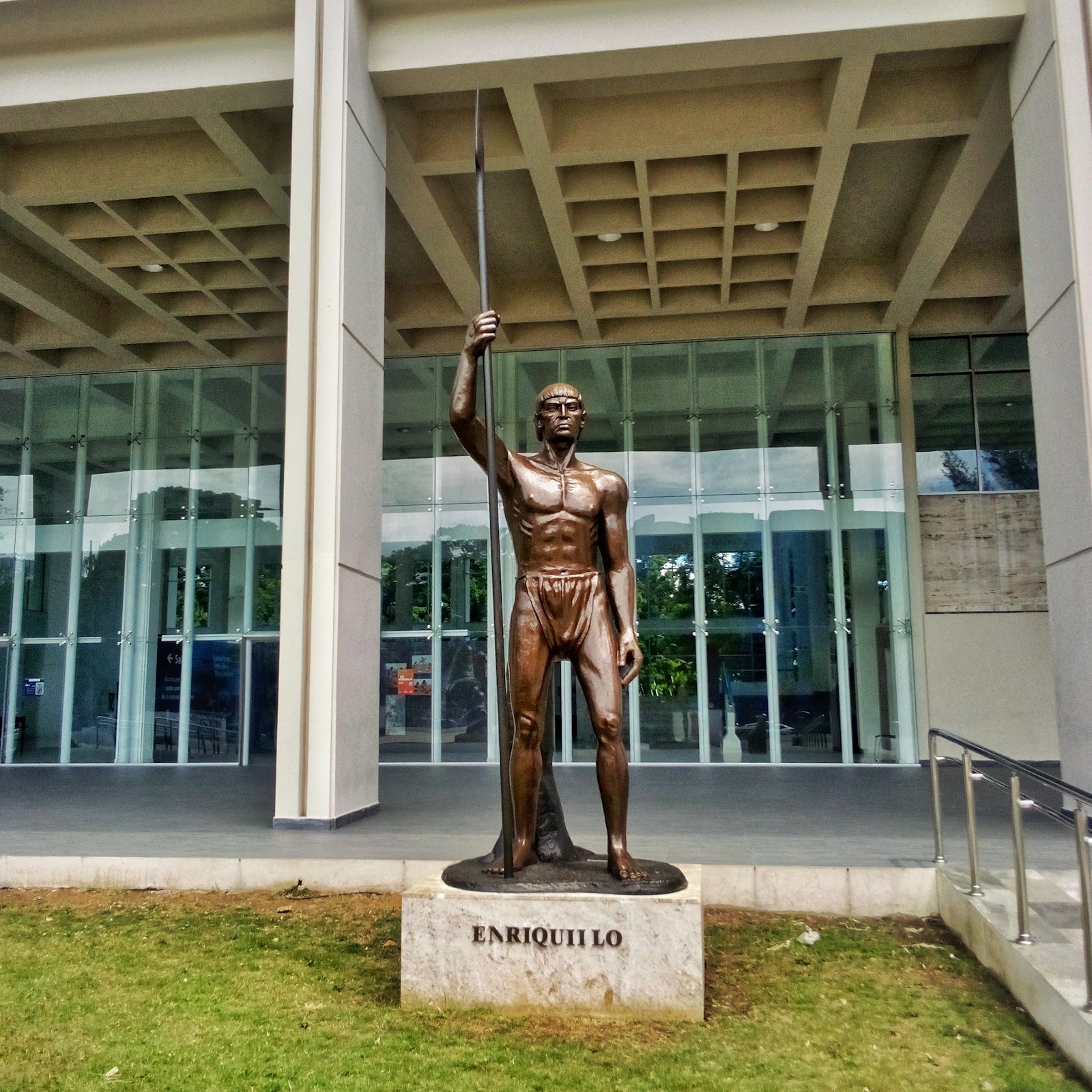

Outside the museum were copper statues of notable historical figures. These statues were recently cleaned, as older photographs show them with a green patina, much like the Statue of Liberty. The middle statue portrayed Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar, who Ferdinand II designated as “Protector of the Indians” in 1544. This realistic depiction of of de las Casas portrayed him wearing his friar robes and holding out a cross, a sharp contrast to the avant-garde version I saw during my ride on ChuChu Colonial. The Dominican hero Sebastián Lemba stood to the left of de las Casas nearer the entrance, breaking his chains over his head. Lemba was an enslaved man from South Africa who led a rebellion in Hispaniola for fifteen years until his execution around 1547. To the right of de las Casas was another Dominican hero, Enriquillo, a Taíno cacique or chief who led his own rebellion against the Spanish after the governor, Frey Nicolás de Ovando, assassinated around eighty members of the Taíno nobility. Like Lemba, Enriquillo did not win the rebellion.

Inside the museum, visitors faced a first floor full of signage. Large vinyl posters contained text, illustrations, maps, diagrams, and photographs of indigenous Caribbean communities and artifacts ranging from first human contact with the islands to the arrival of the Spanish thousands of years later. My biggest takeaway from these exhibits were the number of ethnic groups that came to the islands and displaced the people already living there. While various Taíno and other Arawak people had lived on the islands for generations, Kalinago or Carib people were displacing them during the late 15th century. The longest inhabitants were Guanahatabey people, who were pushed to the far west of Cuba by Arawak people. Each ethnic group had distinct diet and agriculture, artwork and pottery, religion and mythology, tools and weapons.

An elevator took visitors to the second floor of the museum, which held a fraction of the artifacts in the collection. This exhibit, Exposición Temporal Cemíes, Dúhos y Rituales Aborígenes [Temporary Exposition of Cemís, Dúhos, and Aboriginal Rituals], displayed pottery, conch shell horns, and many religious objects. While I had seen some similar artifacts in the permanent Mesoamerican exhibit of the Worcester Art Museum, I had never seen zemí or cemí figures. These figures come in two types: triangular stones, also known by the Spanish name trigonolitos, and humanoid figures. The triangular cemís appear in a range of sizes and represented the spirits of ancestors. Some figures looked like the faces of people, while others looked like animals such as dogs or fish. Each of the three points held symbolic meaning in Taíno religion. The top peak represented a sacred mountain and the four cardinal directions of the sky where the creator god lived. The front peak represented the land of the dead, while the back peak represented the land of the living. The figurine cemís have a bowl on the top of their heads used for holding cohoba, a narcotic snuff that allowed caciques to enter the spirit world. These cemís were paired with dúhos, low wooden or stone seats used by caciques in Taíno religious ceremonies so they could relax after taking cohoba.

This compact museum was a phenominal way to learn precolumbian history directly from the descendents of the first Caribbean people. The signage balanced a global perspective with personal stories, allowing visitors to understand the facts without getting bogged down by a barrage of details. Spanish language signage was written at about a sixth grade reading level with the exception of some technical terms. (Fortunately for me, most of these were derived from Greek and Latin roots with cognates in English.) No audio tour in Spanish or another language was available; my eyes became tired from so much reading. The modern building was fully wheelchair accessibility, although like many museums, the galleries could have used more seating. The first floor was well lit, while the second floor was dark for ambiance. The second floor included imagery of bloodless human sacrifice and ritualist cohoba inhalation, which may bother some visitors. Tickets prices were RD$100 (US$1.75) for adults and RD$20 (US$0.35) for students, once again an amazing bargain for so much history. The museum is open Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., plus Saturday and Sunday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. While the scope of this musuem was super specific and may not be for everyone, I believe this was best location in the world to discover the full spectrum of early Caribbean culture.

Abby Epplett’s Rating System

Experience: 8/10

Accessibility: 8/10